Season wraps up, symposium, nest architecture, carder bees, nectar robbing, and bee food

Season ends September 30th

The weather has started to cool down and many bees have stopped foraging for the year which signals the end of data collection for Shutterbee. The last day to conduct a survey is Saturday, September 30th. If you still have past surveys that you have not uploaded to iNaturalist, please upload them at any time! We will still ID them and use them in our researsch.

Thank you so much to all of you who took time out of your summer to collect data for Shutterbee!!

Announcing the Second Annual Shutterbee Research Symposium

Last year we had so much fun at the research symposium (recap of the event here), we decided to do it again! The symposium will be on November 11th at Webster University. It will be a chance to mingle with other participants and hear talks from your fellow participants and the undergraduate students.

If you are interested in giving a talk about anything related to cities, plants, gardens, wildlife, photography or another relevant topic, please fill out this form by October 11th.

More details to come in the next bulletin.

Ground nesting bee architecture

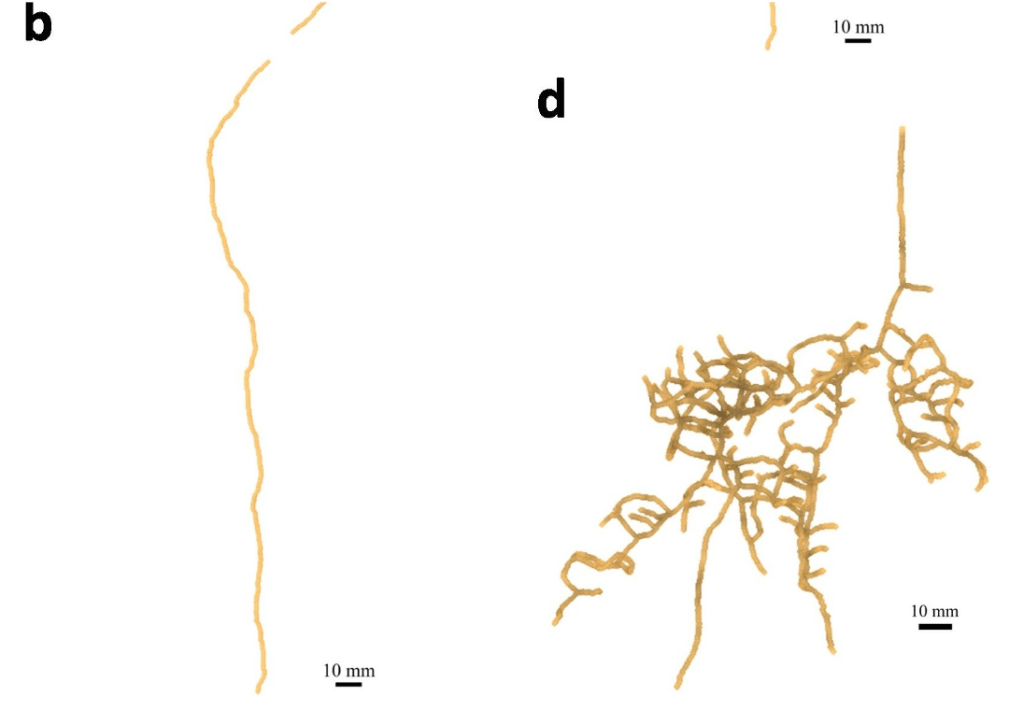

The vast majority of bees nest in the ground, but overall we do not know a lot about the architecture of nests that bees make. This is because it is incredibly labor intensive and difficult to investigate a nest without collapsing it. A recently published paper sought to assess if they could use a CT scanner (yes, they brought the nests into a hospital!) to create a model of the nests. To do this, the researchers shoved a large pipe into the ground around a nest and excavated the nest multiple times to see how it grew over time.

The nests they examined were from two species, and it shows that there is a large variation in the complexity of the nest architecture. The difference is partially due to the behavior of the bees. The simple nest (panel b in the picture below) is from a species that is solitary — one female creates the nest and provisions the eggs over the course of a few days. The complex nest (panel d in the figure below) is from a social species in which the nest is being utilized and maintained by multiple females over a longer period of time. A video of the 3D structure can be found here!

This success of this methodology opens up a new avenue of research in investigating nest architecture diversity and how environmental factors may impact nest building within and among different bee species.

Carder bees love south city

The non-native Anthidium (wool carder) bees in our region––Anthidium manicatum and Anthidium oblongatum––are familiar to many of us because of their “brute” behavior (they like to protect their flowers by bumping off other bees). However, we have many other species of carder and resin bees that are native to the region, including Stelis, Dianthidium and Anthidiellum.

Stelis are fairly common across the region, but interestingly, within the urbanized region, all the recent records of Dianthidium and Anthidiellum have occurred in south St. Louis City. Nina caught a Dianthidium in 2022 in North Hampton, and Shutterbee participants Ron Goetz and Payton Sullivan have the only records of Anthidiellum in the region on iNaturalist which they found at MoBOT and Compton Hill Park, respectively.

So what is it about south city that has allowed these bees to persist? The short answer is we don’t know. These cavity nesting species build their nests with pebbles and/or plant resins, which may be in higher supply in the city. For instance, they could be nesting between bricks and stone walls. They may also benefitting from a large diversity of plantings found in parks and gardens. Hypotheses abound, but we need more research to know for sure!

Photo by Patti Zigler

Nectar Robbing

Did you know that even bees, ever hard-working and diligent, sometimes take shortcuts? Nectar robbing is a fascinating behavior observed in certain bee species. Instead of following the traditional route of pollination by entering a flower through its reproductive structures, nectar-robbing bees employ a more resourceful approach – they puncture holes or access nectar by alternative means, often bypassing the flower’s reproductive organs altogether. This means that no pollination does not occur, and the bee gets the floral resources “for free”.

Why nectar rob? A key reason for this behavior is high efficiency. Bees might resort to this behavior when the effort required to access nectar through legitimate channels is too high, like some flowers with long corolla tubes. While only bees with really strong jaws (like carpenter bees) can create the holes in the flowers required to start nectar robbing, any bee can take advantage of the hole once it is there.

Theoretically, bees are “ripping-off” the flowers that they rob, so to speak. Nectar can be an expensive resource to make and is typically provided for a plant in exchange for pollination services. Without pollination, plants may be at a relative loss. The widespread implications of nectar robbing on a species, however, are not necessarily all that impactful. Some species may have evolved to tolerate nectar robbing by compensating for the loss, while others may make their nectar taste bitter to non-desired species. Overall, ecological context matters when determining the effect that nectar robbers have on the plants they take from.

Bee Food

While it is generally understood that flowers are the very lifeline of bees and many other pollinators, they use plant products for more than just energy. Yes, nectar helps adult bees regain their energy, but they also use nectar to form pollen into a “cake”, which is the primary food source for bee babies. Other bees, such as the wool carder bees, use plant hairs to build the cells in their nests. Not all flower resources are created equal for every species, though. Both pollinators and plants can have specific adaptations that make them suited for each other – or not.

Planting native flora is a great way to ensure native bees can stay happy, healthy, and well-fed. So, if you’re looking for any garden inspiration for next season, below is a very brief list of some bee faves that are endemic to the St. Louis area. We here at Shutterbee think they are also quite pretty to look at, so it is a win-win for all!

The purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) is a vibrant perennial that blooms from May to October. Commonly found in glades and prairies, it prefers well-drained soil and full sun, though it can live with partial shade. It is also drought-tolerant making it a wonderful and low-maintenance garden addition.

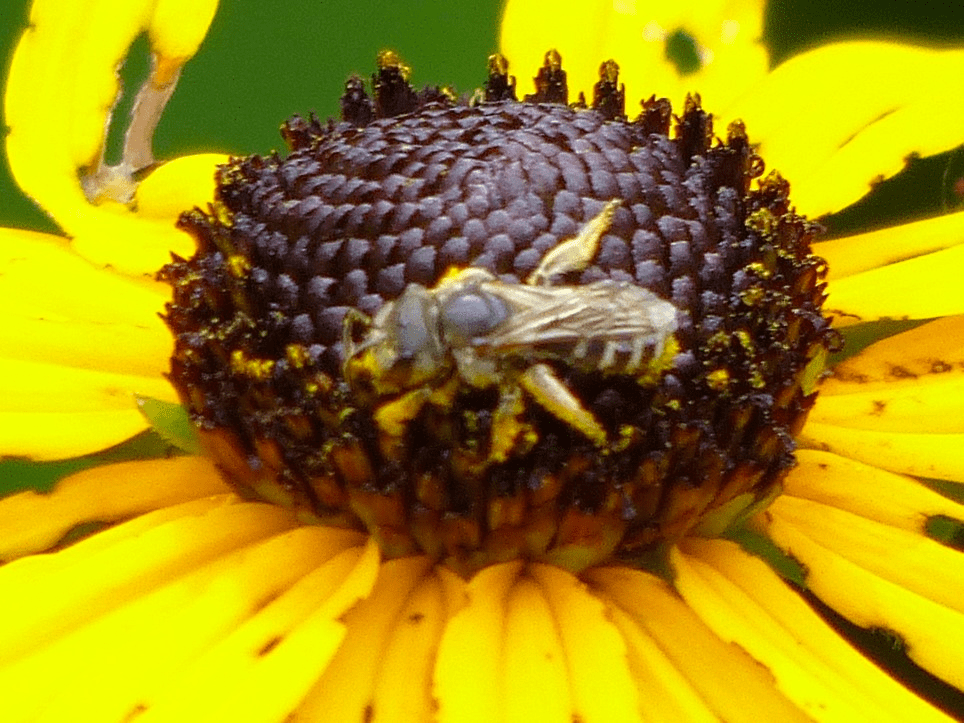

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta) is another May-October glade/prairie native, though it may also be found on the edges of woodlands. While it is a biennial or short-lived perennial, gardeners can encourage additional growth by providing well-drained soil, adequate moisture, and other care like deadheading.

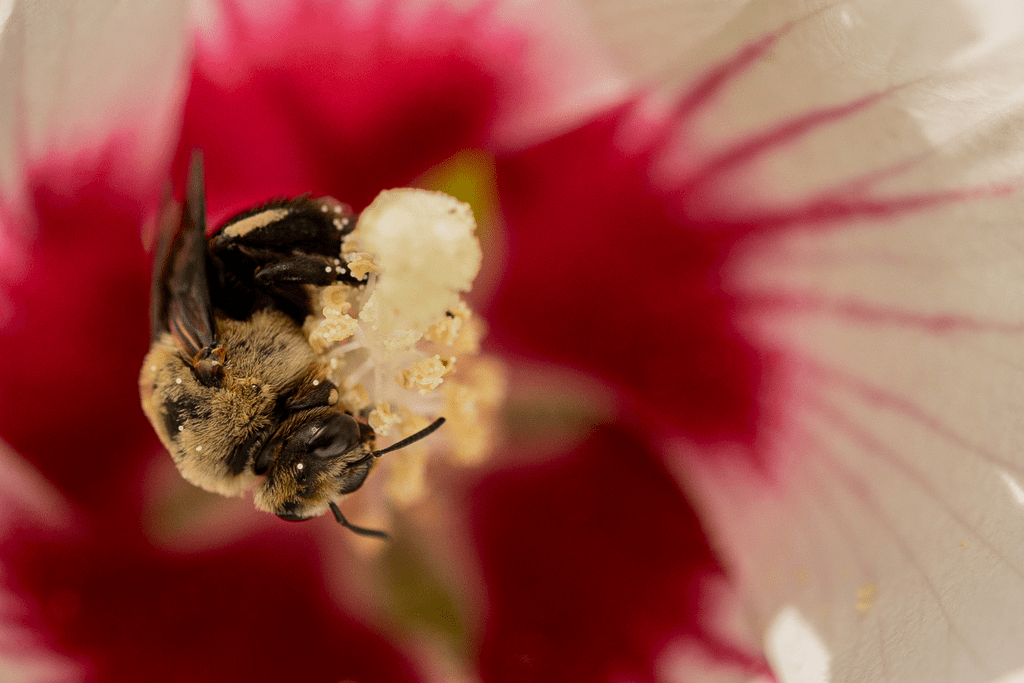

Multiple species of Hibiscus, also known as rose mallows, are perennials native to Missouri. The halberdleaf rosemallow (H. laevis) can get up to 7 feet tall at maturity, and it casts showy blooms from mid-summer to early fall. It prefers full sun to partial shade in addition to well-draining moist soils but is fairly hardy and low maintenance. The flowers attract a wide range of pollinators – such as hibiscus turret bees (see one below)!

Beebalms (Genus Monarda) aren’t named that for nothing – their unique flowers are absolute bee buffets! The Eastern beebalm (Monarda bradburiana) is a low-maintenance, herbaceous perennial that loves full sun or partial shade. They can tolerate drought and shallow, rocky, dry soil, and can reach a height and spread of 2 ft.

Interested in learning what native plants might work best for your garden? Click here to sign up for Bring Conservation Home’s plant consult waitlist!