Farewell to Our Beloved Shutterbee

It is with heavy hearts that we have decided to retire the Shutterbee Citizen Science Project. The project has accomplished more than we could have imaged, and we have enjoyed running it over the last four years. However, it is no longer feasible for us to keep it going.

Shutterbee would have not been successful without each of our participants! Thank you so much for spending your time doing surveys and dutifully entering metadata. Thank you for building community by attending events, sharing cool stories on the Facebook page, and sending us insightful questions. Thank you for incredible images, thoughtful ideas, and amazing gardens. Thank you for making this program something that we looked forward to each summer.

This newsletter serves as a retrospective of what Shutterbee has accomplished over the years, from its initial seeds as program called “Bee Brigade” which focused on bumblebees in Forest Park, to today. We celebrate the Shutterbee community, highlight some of the uncommon bees that we found, and share how Shutterbee has changed our participants and undergraduate assistants. We tell you about several lesson plans that our education team developed, and what’s coming next in terms of future publications and events.

Thank you all so much for everything. We have opened the comment section of this post, so feel free to post a comment if you’d like here or on our Facebook group! We would love to hear your thoughts and reflections.

Sincerely, Nicole and Nina

The Shutterbee Community

Our Amazing Participants

Our participants are the core of this project. Without your dedication––spending hours photographing bees and uploading your observations to iNaturalist––we wouldn’t have a program at all, let alone the strong community and detailed ecological data. 273 of you submitted observations to iNaturalist, 639 different folks identified our bees on iNaturalist, and 547 people learned about bees through the Bee Bulletin. In total, the project has 37,000+ observations of bees taken during surveys that meet our rigorous research standards. Participants conducted from 1 to 102 surveys and recorded up to 1530 individual bees (average = 135). More than half of you returned year after year — some participating all 4 years, which is incredible for any citizen science project, let alone one as labor intensive as Shutterbee.

Your enthusiasm was infectious! You helped to grow our program by sharing your experiences with your friends and neighbors. Every year, we had new participants join, many indicating that they learned about the program through word of mouth. You learned from each other, shared your thoughts and ideas with us, and built community around bees, gardening, and conservation. Many of you changed as a result of the program (see the “Your Participation Built Agency” section below), and we changed as a result of you. Thank you so much for commitment to the program and for sharing your energy, time, and joy with us.

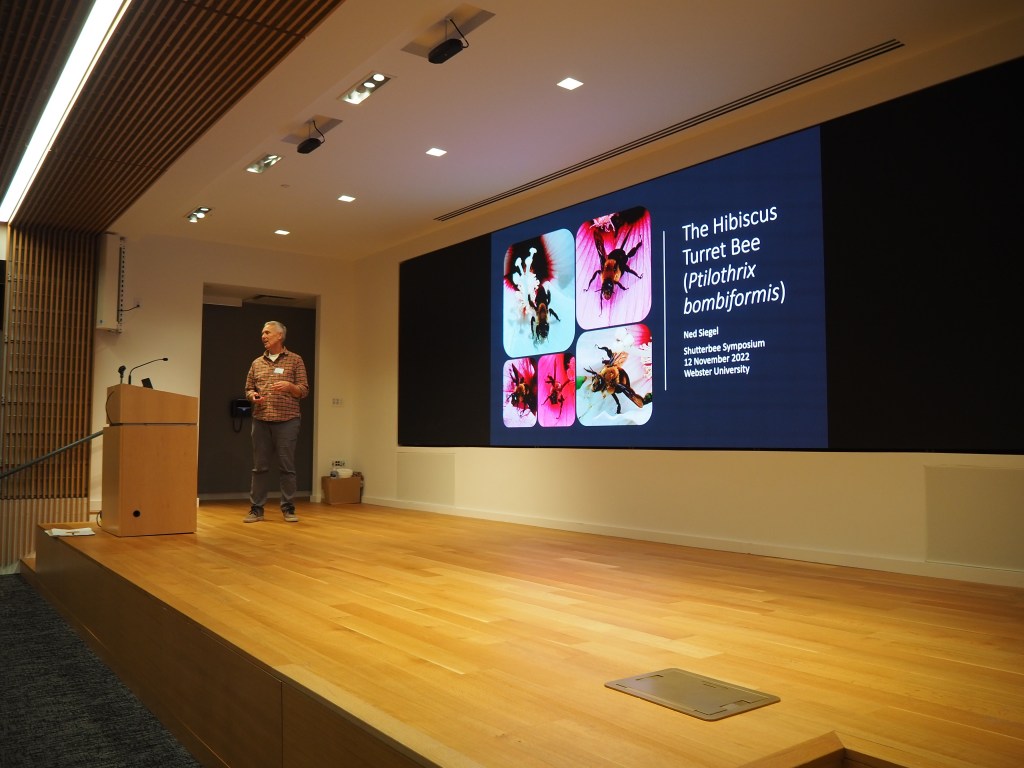

In-Person Events and Celebrations

We’ve put on some fun events over the years! We got off to a slow start in 2020 for obvious reasons, but since then we’ve had Bee Blitzes at Forest Park, two Shutterbee Symposiums (Recap of 2022, Recap of 2023), and let’s not forget Nina’s dissertation defense! It was always a pleasure to learn from each of you, hear about your gardens and your Shutterbee experience, and celebrate the bees. Thank you to all of you who came out to make these events a success!

Bee Identification Classes

Once we saw how eager all of you were to identify bees, we knew we had to provide some resources to help. We created the bee identification guide with decision trees. Don’t worry, it’s not going away! We taught the guide three times via a series of Zoom classes. In 2023, we had an in-person course where participants could practice their skills by looking at real specimens under a microscope. If identifying bees (or any other organism) is something you’re still interested in, there’s a great community on iNaturalist that will help you refine your skills and offer advice.

Our bee identification guide as well as other guides will remain on the Identifying Bees page.

Your Participation Built Agency

In collaboration with Erin Tate at the Saint Louis Zoo, we gathered 103 responses to a participant survey that assessed changes in attitudes, knowledge, and behavior before and after at least one season of data collection. Our goal was to understand how involvement with Shutterbee affected the participants themselves.

The first element that we looked at was Environmental Identity, which is the strength of one’s perception of self as they relate to nature. Shutterbee citizen scientists entered the program with Environmental Identities already higher than the US average. However, there’s always room to grow — Shutterbee participants’s Environmental Identity increased significantly after participation in just one season! Interestingly, the number of different bee species observed didn’t affect these trends. Regardless of whether participants saw a few kinds of bees or many kinds of bees, they still received the same benefit -– a reinforced relationship with nature.

Shifts in influences in participant’s planting decisions also demonstrate the power of social norms centered around native biodiversity. Prior to participation, Shutterbee citizen scientists felt they either relied on personal or neighbor preference or had no outside influences at all. After one season of data collection, participants collectively shifted towards valuing conservation organizations, like Missouri Botanical Garden or Wild Ones, over personal preference. This effect was compounded in participants who were involved both in Bring Conservation Home and Shutterbee, demonstrating the power of reinforcement in encouraging pro-environmental behaviors like planting native.

Shutterbee survey participants also showed a significant increase in low-effort environmental actions (conserving energy and water) and high-effort actions (switching to ecologically friendly products, reusing and sorting recyclables). While these actions may not directly benefit backyard biodiversity, the relationship between citizen scientists’ increased action and program participation is encouraging. It implies that the impacts of participation in a bee-related citizen science program extend not only to bee conservation but to other environmental issues. Importantly, participants’ feelings of self-efficacy, or the belief that they have the agency to make a difference, increased significantly after at least one season of participation.

Shutterbee participants have grown during their time as citizen scientists. Collectively, your relationships with nature, wildlife, and these bees have been reinforced as a result of participating, and your dedication to caring for our local backyard biodiversity is stronger as a result. Just like you made Shutterbee better, you make St. Louis a better place for bees – thank you.

Additional thanks to Shutterbee Survey interns Briana Robles, Scott Lovell, Haley Minnerath-Moore, and Coral Martin for their hard work and enthusiasm in analyzing and interpreting preliminary findings.

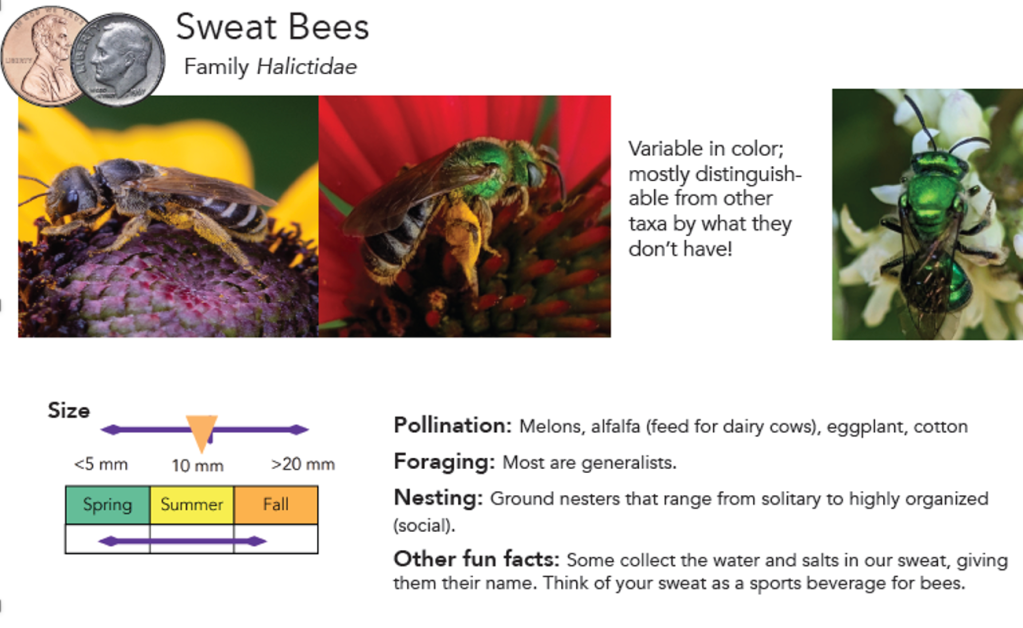

Cool Bees You Found

This project was intended to look at the entire bee community and plant-pollinator interactions. But that doesn’t mean we didn’t find some cool individual bees! Each bee species is unique, reflecting millions of years of evolution, and St. Louis has a relatively large diversity (over 200!). You found many common and uncommon species in your gardens (N = 115 species + 40 bees at genus or subgenus level). Below, we highlight some of the uncommon bees (at least in urban areas) that were found during Shutterbee surveys:

B: Colletes aestivalis, found by Chris Kirmaier

C: Stelis lateralis, found by Ilya Buldyrev

D: Andrena cerebrata, found by Sue Nixon

E: Bombus citrinus, found by Ned Siegel

F: Protandrena passiflorae, found by Kathy Bildner

G: Nomia nortoni, found by 2 people, photo by Marion Miller

H: Dieunomia nevadensis, found by Michael Wohlstadter

Transformative Experiences for Undergraduates

This project would not have been successful without the 28 fantastic undergrads that have worked on the project over the years. Webster undergrads designed the logo, built the website, identified bees on iNaturalist, sent emails, wrote the newsletter, collected data, curated data, and did their own analyses. Most of them have put together posters and presented their research in some capacity, whether it was the Shutterbee Symposium, as a senior thesis, or at the Botanical and/or Ecological Society for America conferences.

Here are a few (lightly edited) quotes from undergraduate collaborators on their experiences with Shutterbee:

Thanks to Shutterbee, I know way more about bees than I ever thought I wanted to know (and get to bother people with my bee facts). My coworkers now consider me the ‘bee lady’. Working on the project also got me very interested in plants and the relationships between native plants and our native bees and other wildlife. I now specialize in midwest native plants and it is now one of my biggest dreams to create a platinum-level certified property through the Bring Conservation Home program. I can’t thank Shutterbee enough for what it has taught me, and the course it helped to set for my future. ~ 2020 Research Assistant

It was my first real research experience and helped inform what I wanted to pursue in my career. I certainly would not be in graduate school or had the experiences I did during my undergraduate career without Shutterbee. ~2021 Research Assistant

Shutterbee has broadened my perspectives, heightened my love for the environment, and sparked a bigger interest in supporting our pollinators. Shutterbee is not just an initiative; it is a source of inspiration that has shaped my personal and professional journey. ~ 2023 Research Assistant

It was a joy to work with you and to watch you grow as scientists. We love getting updates from you and look forward to hearing about where you go next!

Spreading Bee Love to the Next Generation

In collaboration with Michael Dawson (Saint Louis Zoo), Jennifer Gauble (Saint Louis Zoo), and James Faupel (Missouri Botanical Garden), we designed and tested three educational activities! These activities use active learning strategies to help students understand the role of bees in pollinating our food plants, why diversity of pollinators matters, and how to distinguish among some common bee pollinators.

Each lesson is aligned with the Missouri Science Learning Standards 6-8 Grade Level Expectations and the North American Association for Environmental Education Guidelines for Excellence Grades 5-8. While designed to be used together, these lessons can use separately with minimal modification.

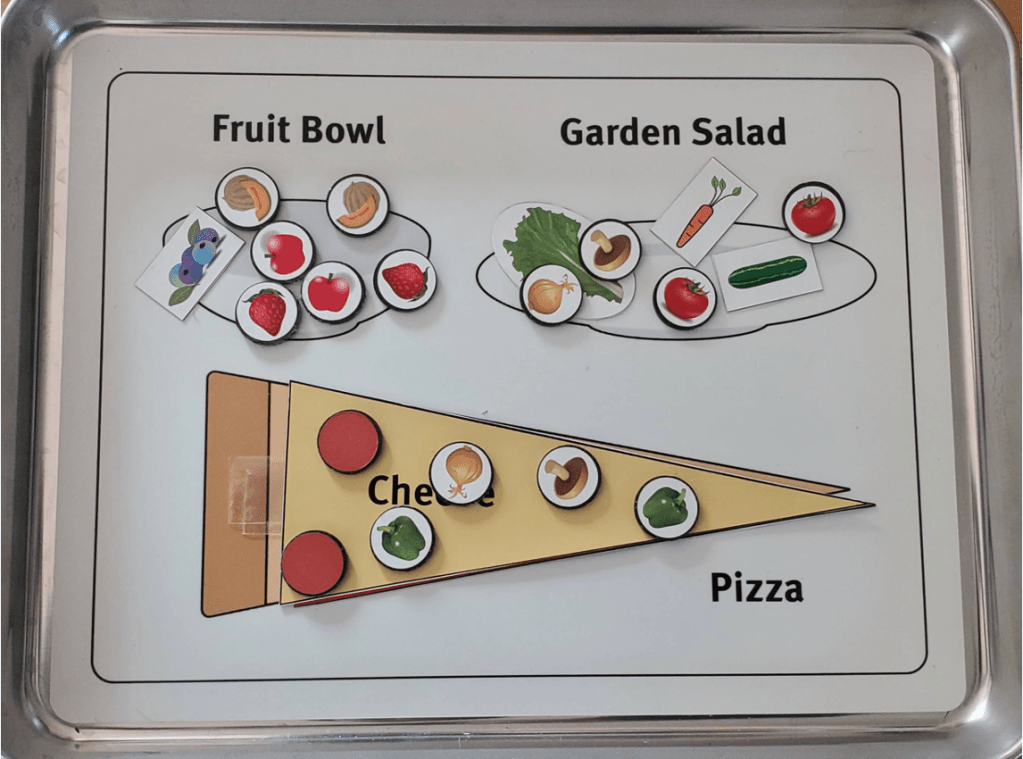

Activity 1 sets the stage by first demonstrating why pollinators are important. Students build a lunch and then dismantle their meal based on the loss of pollinators. They then learn some basic insect biology by building models of bees and bee and wasp mimics.

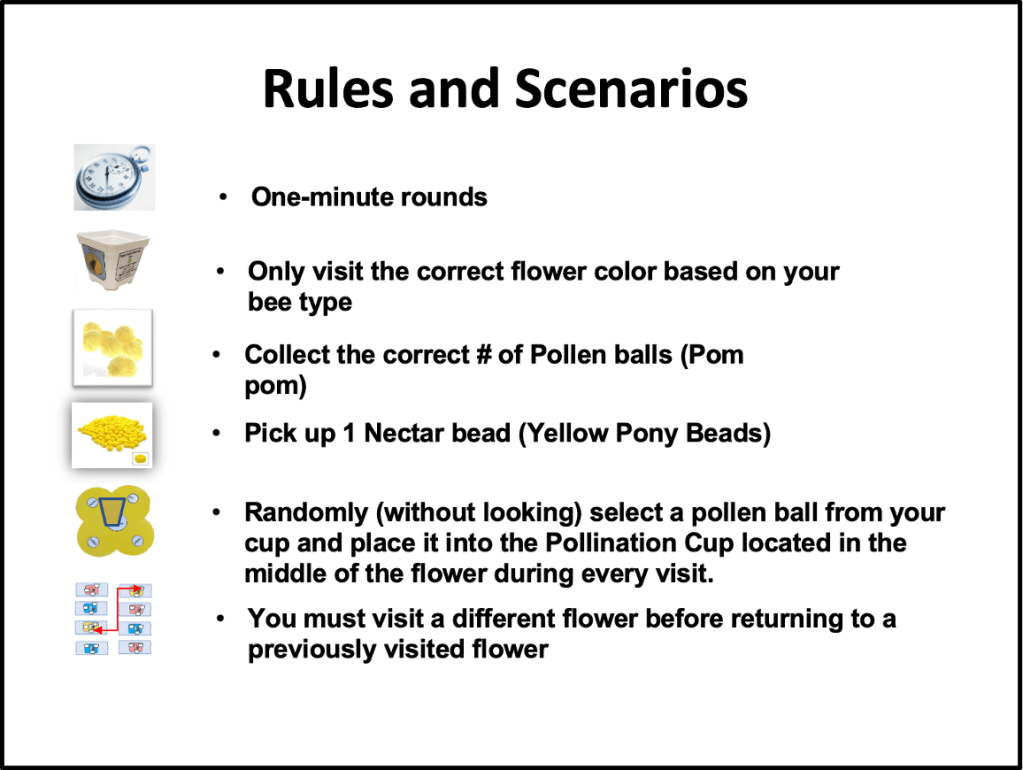

Activity 2 is a game where students act as bees pollinating plants. They have to quickly visit flowers, competing for the available pollen and nectar resources before they are depleted, to survive. Students simulate what happens when when a specialist sunflower bee goes extinct and graph their results.

Activity 3 challenges more advanced students to become citizen scientists, photographing bees and using decision trees to identify them. Students then dig deeper into bee anatomy and natural history by teaching their peers about the bees they found.

The activities are available, in full, on the Educational Activities page of this website. Check ’em out. Use them. Share them with a friend. We are happy to assist, so please don’t hesitate to reach out to Nicole (shutterbee@webster.edu) if you have questions or would like support in using them.

Research Findings

Your Data Rules! (aka Photo Surveys Predict Netting Data)

Citizen science projects usually have two goals: first, to do community outreach and second, to generate data that can be used to answer research questions. The Shutterbee methodology of doing timed, systematic photo surveys have never been done before, so we had to test its effectiveness. First, we needed to see how photography compared to netting, which is one of the best ways to sample bee diversity. We trained our amazing undergraduate research assistants how to do the Shutterbee protocol and then compared their surveys done at 44 locations to that of netting. Overall, there was a very high agreement between the two methodologies. The undergrads documented generally the same number and relative abundance of each bee taxa as we observed with the netting, which means photo surveys are affective at documenting bee diversity!

Next, we wanted to see if Shutterbee participants could perform the protocol as well as the research assistants. This time, we compared the undergraduate’s surveys to 106 participants. While the undergrads photographed more bees overall, there was high agreement in the proportions of each taxa photographed. Meaning that you all do an excellent job documenting bee diversity in your yards! Each participant varied in how closely their specific survey results compared to the undergrad’s (some documented fewer species, others documented more, and some were even-steven), but we were overall really pleased with the results. Being able to collect data on par with people with more training than you is really quite a feat! We are currently writing a manuscript on this work and hope to encourage others to use this non-lethal approach whenever possible.

Garden Quality Reduces the Effects of Suburbanization

You may be asking yourself, what is “suburbanization”? We often use the term urbanization to describe the multiple environmental changes that come along with high human population density. However, that term carries a negative connotation, with many assuming that diversity is lower in the city. For bees though, it is the opposite––bee diversity is higher in the city than adjacent rural areas. It is the suburbs where diversity declines relative to more urban areas. We were interested in understanding why that might be the case. Does it have to do with regional factors, like how many people live in an area or how much concrete there is? Or are local factors, like plant diversity, more important?

For our St. Louis gardens, the answer is both. Bee richness and the number of bee-plant interactions are lower in suburban residential gardens relative to those in the city. However, local conditions, such as the number and type of flowers that you have in your garden, can reduce those negative effects. High quality gardens have higher bee diversity and more complex bee-plant interaction networks, despite being in a suburban landscape.

Interestingly, differences in bee species composition among gardens isn’t affected by suburbanization. As you move from city garden to city garden, you see more bees per garden than in the ‘burbs. However, you don’t see more unique species as you move between them. This supports the idea that what is going on locally in your garden matters more for bee diversity than regional conditions, such as the amount of concrete in your neighborhood.

However, there are still some differences among communities in the cities vs. the suburbs. Non-native bees, like the wool carder bees, are more likely to be found in the city. Indeed, geography might be more important than either “urban-ness” or local habitat quality. While we do not have enough non-native species in the region to test this more formally, our native species do not show similar patterns, suggesting it may be a trend unique to non-native taxa.

We will be continuing to analyze these data and preparing them for publication. We will keep you updated on our progress and will share any formal write-ups with you as the emerge. In the mean time, you can find more details on our research results, including presentation recordings and research posters, in the Research Updates section here.

We want to give a special thanks to all of our Shutterbee Participants, Science Ambassadors, and Research Assistants – without whom this research would never have been possible. Each of you contributed a critical piece toward these results. In particular, we want to recognize that analytical work discussed above was driven by Cheyenne Davis, Emily Buerhle, Jessica Clones, Josh Felton, Evelyn Gerrero, Colby Kapp, Jason Pho, and Sampurna Lamichhane.

A few of the many biodiverse gardens managed and photographed by Shutterbee Citizen Scientists.

What’s Next

While the data collection is officially ending, we will continue to explore the secrets these data hold and will share those results with you, likely for years to come. Nicole will be continuing in her role at Webster and as a community liaison (you haven’t heard the last of me 😉), and Nina will likely always be on iNaturalist, but is currently figuring out what’s next for employment (please write her at nina.fogel@slu.edu if you hear of any neat conservation-focused jobs).

In the meantime, we have one last special event planned! The Webster University’s Kooyumjian Gallery will be hosting an art opening including some of YOUR photos! The exhibit will open in October 2024, alongside the work of celebrated Missouri nature photographer Noppadol Paothong. Noppadol is an associate fellow with the International League of Conservation Photographers (iLCP) and a staff wildlife photographer for the Missouri Department of Conservation. His images appear regularly in many national publications (e.g., Audubon, Nature Conservancy, National Wildlife, Ranger Rick) and closer to home in the Missouri Conservationist and Xplor magazine. It is an honor to have our photos alongside his work. We will have a celebratory event when the exhibit opens and hope you can all attend. We will keep you posted!

Other Citizen Science Projects to Fill the Void

Shutterbee is ending, but that doesn’t mean you can’t still take photos of bees if you’d like (no metadata required) and post them on iNaturalist. Nina is still addicted to iNaturalist, so she will likely ID your bees at some point.

If you’d like to continue to be a part of a structured project, here are a few we’ve rounded up in the region:

Bumblebee Atlas Missouri: run by the Xerces society, it involves netting, photographing and then releasing bumblebees. Link to program here.

Missouri Stream Team and Illinois Riverwatch: Monitor water quality and aquatic species around the state. MO program here. IL program here

FrogWatch: This project has multiple ways you can help track frog populations around the region (MO only). Link to program here

Great Sunflower Project: plant a sunflower and count how many insects visit it. Link to program here

Monarch and Pollinators on Ornamental Plants: Collect data on monarch abundance and what pollinators visit non-native ornamental plants. These two projects are run through University of Illinois (IL only). Link to projects here

Caterpillar Count: Count caterpillars and beetles on trees to understand how abundances change throughout the year. Link to project here

There’s also some great conservation and science-oriented organization that may be of interest to you if you want to continue to learn about the world around you and be around like-minded folks. These organizations include St. Louis Audubon, Webster Groves Nature Study Society (not just for people who live in Webster Groves!), and Wild Ones with chapters in St. Louis, St. Charles and the Metro East.

Photo Album

One response to “March 2024”

👏👏👏👏👏🥲